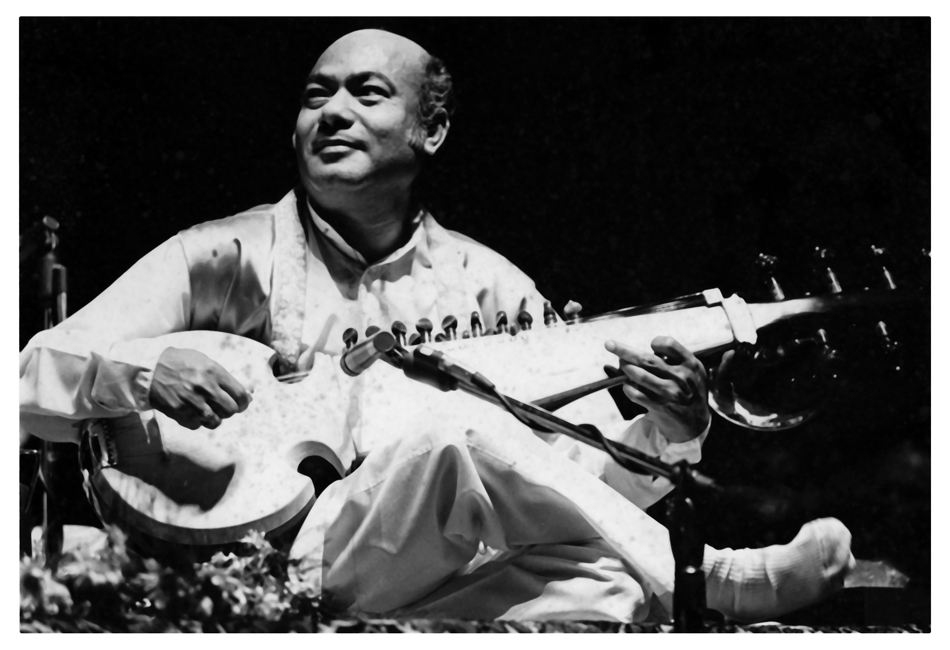

Ravi Shankar (center), Alla Rakha (left) and Tanpura accompanist (right)

“Indian Classical Music is one of the finest ancient art forms of the world. Part from its beauty and entertaining qualities as a pure performing art, its spiritual propensity as well as its ability to positively affect and enhance one’s mental intellectual capacities in multiple ways is well acknowledged.” - Samarth Nagarkar, Raga Sangeet

Popularized in the west through the efforts of sitar player Ravi Shankar and his tabla (twin-drum) accompanist Alla Rakha, Indian classical music is a rich musical tradition filled with complexity. Performance of Indian classical music requires many years of study and discipline. In order to master the fundamental techniques, and feel their resonance within oneself, the teacher to student (guru-shishya) relationship is of paramount importance. Becoming immersed in raga theory and practice, a student learns primarily through oral means by listening and learning the tradition passed down from his or her guru. Many years of dedicated training is needed between the guru and his disciple before these building blocks can be fully accomplished but, once they are, the advanced principles can be merged to create one beautifully balanced exhibition of a raga.

Listen to an excerpt from Samarth Nagarkar's Raga Improvisation class at Sacred Arts Research Foundation:

Styles of Indian classical music

There are two main styles of Indian classical music, Hindustani Classical Music (North Indian) and Carnatic Classical Music (South Indian). Each of these styles has a unique set of instruments and sonic characteristics. The intention behind the music, however, is the same. Historically, in the early years, Indian music traditions would be carried on through a lineage known as a gharana, literally meaning ‘family’. In the early 19th century, gharanas came to be formed by adhering to stylistic peculiarities and innovations of certain musicians by other musicians within their families or regions. The name chosen for each gharana usually reflected the kingdoms or regions to which the musicians came from to indicate their roots. Hence, a few of the most prominent gharanas are referred to by such names as Agra, Jaipur and Gwalior.

Styles of Indian classical music

There are two main styles of Indian classical music, Hindustani Classical Music (North Indian) and Carnatic Classical Music (South Indian). Each of these styles has a unique set of instruments and sonic characteristics. The intention behind the music, however, is the same. Historically, in the early years, Indian music traditions would be carried on through a lineage known as a gharana, literally meaning ‘family’. In the early 19th century, gharanas came to be formed by adhering to stylistic peculiarities and innovations of certain musicians by other musicians within their families or regions. The name chosen for each gharana usually reflected the kingdoms or regions to which the musicians came from to indicate their roots. Hence, a few of the most prominent gharanas are referred to by such names as Agra, Jaipur and Gwalior.

Ali Akbar Khan

What is raga?

Raga, literally interpreted as “that which colors the mind,” is the fundamental structure within Indian Classical Music. The easiest way for westerners to conceive of a raga is as a distinct melodic form containing certain key movements, each embodying a particular personality of their own. The primary aspects of these movements, the standardized notes (swara) and the rhythm and time (laya), are combined to create unique musical possibilities, each personalized by their own embellishment techniques. To complete a structural composition, two more essential qualities are included: the tala, which refers to the cyclical system of beats and sahitya, the lyrics, which could be sung vocally or played on instruments through a non-verbal language.

Understanding raga composition

A composition of Hindustani Classical Music is known as a bandish, which literally means ‘binding’. Each bandish consists of a unique blend of the five central elements in Indian classical music:

- notes (swara)

- time (laya)

- rhythm (tala)

- structure (raga)

- lyrics (sahitya)

The composition is the face of the raga, defining its essence by bringing together all of its movements, parts and subtleties. There are two parts to a bandish, each containing two or three lines and lasting only around one to two minutes each within an extended performance (anywhere from twenty minutes to an hour). The majority of the performance is left primarily for improvisation, which is based off the compositional foundation exhibited in the composition. There are countless compositions in Indian Classical Music, each showcasing certain characteristics, phrases and musical personalities but no raga performance will be played or heard exactly the same. They might have similar compositional structures, however they will always be played differently due to improvisation methods and the moods that effect how the musician performs.

Bismillah Khan

The power of a raga composition lies in its ability to evoke emotion that captivates listeners. Originating out of ancient Vedic recitation techniques, the spiritual significance behind Hindustani Classical Music as a whole derives from the philosophical idea of the nāda, the primordial vibration that all life is created from. This “first sound” is associated with the prime cause of the universe and the origin of all manifestation. When a performer sings or plays a raga, his or her intention is as much metaphysical as it is physical. On a technical level, the performer will strive to deliver the raga to its fullest extent to create a complete and well-rounded exposition. The spiritual dimension gives the performer the capacity to dissolve his or her ego in the raga as he or she brings emotion (sorrow, pleasure, anger, etc.) in to enliven the music. By the end of the performance, the adept performer connects with the raga such that the separation between the player and what is being played will be almost seamless, residing in a oneness of energy.

Raga and Time of Day

Traditionally, ragas are played according to the time of day. The Hindustani system associates specific ragas within eight 3-hour periods throughout a 24-hour cycle. These are:

- 4 a.m. - 7 a.m. Dawn (before sunrise)

- 7 a.m. - 10 a.m. Early Morning

- 10 a.m. - 1 p.m. Late Morning/Early Afternoon

- 1 p.m. - 4 p.m. Afternoon/Late Afternoon

- 4 p.m. - 7 p.m. Twilight/Dusk (sunset)

- 7 p.m. - 10 p.m. Evening

- 10 p.m. - 1 a.m. Night

- 1 a.m. - 4 a.m Late Night

More simply, there are two sets of ragas, the morning and the evening, each divided by the effects they had on the human senses. Theories say the time of day system traditionally was due to an aesthetic progression evolving from society’s close connection to nature that was present long ago. This allowed musicians and listeners to clearly identify with certain moods and feel how the ragas effected their emotions at different times. Today, The raga-time tradition is still followed to an extent but general consensus now allows for a 2-hour window outside of the actual time allocated for the raga. For instance, if a raga is supposed to be sung broadly between 7-10 PM, and more specifically between 7-8 PM, a 6 PM or 9 PM rendition is permissible. Due to the technological age that people live presently, our conventional lifestyle has led to a disconnect from the natural forces around us which hinders the ability to feel pure emotions and be able to identify with music that essentially is meant for certain moments. For Indian Classical Musicians, the raga-time tradition is still observed.

Umakant Gundecha and Ramakant Gundecha (Gundecha Brothers)

Indian classical music at present day

Today, there are around 500 known ragas that exist in the world. About 150 are very common and played regularly and the rest are not so known or even not published at all. There are numerous online databases, such as Rajan Parrikar Library and the Swarganga Music Foundation which contain archives of raga recordings and information on Indian classical music. In present times, these microcosmic traditions within the greater tradition that is Indian Classical Music have become fabricated to extent that students now will find that a lot of their practice is mixture of ideas and techniques, all sprouting from the ancient foundation. It is important understand that diversity is a key aspect to learning this musical practice and to keep an open mind to its evolving nature, accepting all interpretations is crucial for ones own musical journey and growth as an intellectual. For students, learning takes time and a great guru to develop the sensitivities and balance to be able to discern what inputs to take and what to leave out. However, if the right intention is kept and the dedication to the practice of learning this music is fully embodied through the guru-shishya training relationship, then before long the student will become one with the raga, dissolving in its vibrational essence and healing all who listens. []

Author FORREST NEUMANN spent the greater part of the past four years traveling extensively throughout the world as a full-time LIU Global student. Raised in California, Forrest's greatest interest is in studying indigenous music traditions, spirituality and healing. Recent studies in India and Peru gave Forrest an opportunity to learn with indigenous spiritual teachers to go deeper into the study of sacred traditions. Forrest loves to DJ and bring people together through melodic healing sounds while restoring human connection with the earth.

SAMARTH NAGARKAR served as editorial advisor for this article. If you would like to learn more about Indian Classical Music and Raga structure, please refer to Mr. Nagarkar’s book Raga Sangeet.